Patent Filing in the United States:

A Comprehensive Guide to the USA Patent Filing Process

For anyone looking to apply for a patent in the United States, understanding the end-to-end USPTO patent process is crucial. This guide explains how to patent an invention in the USA, from the types of patents available to the procedures for patent application in the United States, including direct filings and the PCT national phase in the United States. We’ll cover every step, provisional applications, non-provisional filings, patent examination procedures, publication, and grant, along with key timelines and strategic tips. By the end, you’ll know how to file a patent in the United States effectively and navigate the system to secure patent protection in the USA.

Table of Contents

- Why It Is Important to File a Patent in the United States

- Overview of Patent Types in the United States

- United States Standard Utility Patent Process Timeline

- Patent Filing Routes in the United States: Direct Filing vs PCT National Phase

- Provisional vs. Non-Provisional Patent Applications in the USA

- Patent Filing Process in the United States

- Strategies and Recommendations for Patent Filing in the United States

Why It Is Important to File a Patent in the United States

Filing a patent in the United States secures exclusive rights in the world’s largest and most influential innovation market, representing nearly 25% of global GDP and home to leading technology and life science companies. A U.S. patent not only blocks competitors from using your invention but also becomes a high-value business asset, strengthening your position in negotiations, attracting investors, and increasing company valuation.

A granted patent in the U.S. deters imitation, supports licensing, and gives you a competitive edge while you commercialize your invention. Even a pending patent application in the United States can signal innovation leadership and attract potential partners. Programs such as Track One prioritized examination allow applicants to secure protection in under a year, a key advantage in fast-moving industries.

Finally, U.S. protection serves as a cornerstone for global IP portfolios. Whether filed directly or via the PCT national phase in the United States, it reinforces your international strategy and credibility.

Key Insight: A U.S. patent is one of the world’s most valuable IP assets, driving business growth, attracting investment, and anchoring global patent protection.

Overview of Patent Types in the United States

The United States offers two main types of patents, Utility Patents and Design Patents. Each type of patent protects a different kind of invention:

1. Utility Patents

A utility patent is the most common type of patent in the U.S. It covers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or a new and useful improvement thereof (USPTO). In other words, utility patents protect how an invention works or is used, its functional and structural aspects. Most technical inventions (mechanical devices, electronics, software processes, chemical compounds, etc.) fall under this category. Utility patents are often what people mean by “patent” in general, and they provide broad protection for the functional features of an invention.

2. Design Patents

A design patent protects the ornamental design, shape, or appearance of an article of manufacture, not its function (USPTO). If your invention is about a unique visual appearance, for example, a new furniture design, a distinctive product shape, or user interface icon), a design patent is the appropriate protection. Design patents are much narrower than utility patents, as they only cover the specific look of the object as shown in the patent drawings, and not any functional aspects.

Key Insight

Utility patents in the United States protect what an invention does or how it works, offering broad coverage for functional innovations. Design patents, on the other hand, protect the visual aesthetics of a product, its unique look or shape, rather than its function.

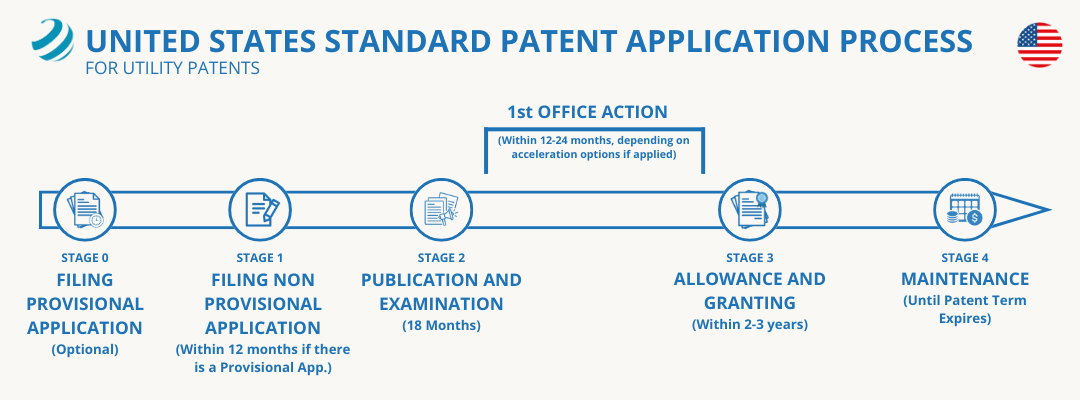

United States Standard Utility Patent Process Timeline

The USPTO patent application process involves several key stages from initial filing to examination, publication, and ultimately grant (or rejection). Below, we outline the process for a typical United States Utility Patent application.

As illustrated above, a U.S. Utility Patent application goes through a life cycle that begins with filing, proceeds through examination (with potential back-and-forth between the applicant and the examiner), results in either allowance (grant) or abandonment, and if granted, extends into a post-grant maintenance phase and eventual expiration.

Patent Filing Routes in the United States: Direct Filing vs PCT National Phase

When you want to file a patent in the United States, there are multiple routes to consider depending on your situation and international plans. The two primary routes are direct U.S. filing and entering the PCT national phase in United States.

1. Direct National Filing or Paris Route

A Direct Filing means you file your patent application directly with the USPTO. If you have not filed elsewhere yet, this could be your first filing. If you have filed in another country and want to file in the U.S., you can file a direct U.S. application within 12 months of your earliest priority date, claiming priority under the Paris Convention.

In a direct filing, you prepare the U.S. application in English, meeting all USPTO formal requirements, and submit it to the USPTO with the required fees. The application will receive a U.S. serial number and proceed through normal U.S. examination. Direct filing is typically faster to get into examination than the PCT route, since you don’t go through the international phase delay, but it commits you to the U.S. early. If you only care about U.S. patent protection, and perhaps a few individual foreign countries via separate filings, direct filing is a straightforward route.

2. PCT National Phase Entry

If you have filed an international application under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) designating the US, you can enter the US national phase to pursue a U.S. patent from that PCT application. The PCT process is often used to file one application that can later be nationalized in many countries. For the U.S., the deadline to enter the national phase is generally 30 months from the earliest priority date of the PCT application (USPTO). To enter the U.S. national stage, you will need to file following the required process and submit any required documents not already in the international

application (such as an English translation if the PCT was not in English, an oath/declaration by the inventor, and U.S. claims if you wish to amend them). The U.S. national stage application will then be treated much like a direct-filed U.S. application, receiving a U.S. serial number and undergoing USPTO examination.

Choosing between direct filing and PCT national phase depends on your needs. If you want protection only in the U.S., or you want to start U.S. examination quickly, a direct filing is simpler and faster. If you are pursuing a global patent strategy and used the PCT to keep options open worldwide, you’ll enter the U.S. via the national phase at 30 months. Keep in mind that a PCT doesn’t give you a patent by itself, it’s a placeholder that must be followed by national filings like the U.S. to actually get patents. The advantage of the PCT route is that it delays the major costs and decisions about where to file by up to 2.5 years, while providing an international search report and preliminary examination that can inform your chances.

Key Insight

Applicants have two main pathways for U.S. patent filing: file directly with the USPTO, or file internationally via the PCT and enter the U.S. national stage within 30 months. Direct filing is immediate and often used if the U.S. is a primary target, while the PCT route buys time and flexibility for foreign filings (including the U.S.). Choose the route that fits your international strategy and timeline.

Provisional vs. Non-Provisional Patent Applications in the USA

When pursuing a Utility Patent in the United States, inventors often encounter two application types: provisional and non-provisional patent applications. It’s important to understand the difference.

1. Provisional Patent Application

A Provisional Patent Application is a temporary placeholder filing. It lets you secure a priority filing date for your invention at low cost and with minimal formality. A provisional application is not examined by the USPTO. Think of it as a 12-month “hold” on your invention’s place in line.

Filing a provisional is useful if you need more time to refine the invention, seek funding, or prepare a full application while immediately locking in a filing date. In the U.S., a provisional patent application lasts 12 months and must be converted into a non-provisional application within that period to preserve the priority date. Notably, design patents cannot be filed provisionally, the provisional route is available for utility inventions only.

2. Non-Provisional Patent Application

A Non-Provisional Patent Application is the formal patent application that gets examined by the USPTO and can lead to an issued patent. A non-provisional application requires a complete description, claims, drawings, an oath/declaration, and payment of filing, search, and examination fees. You can file a non-provisional application directly, with or without an earlier provisional, or as a follow-up to a provisional. Once filed, the non-provisional application is assigned to an examiner and will go through the full examination process. This is the application that can result in a granted patent if all requirements are met.

Important: If you do file a provisional, remember that you must file the non-provisional within 12 months of the provisional’s filing date to claim its priority. The provisional itself expires after 12 months and is never published or examined, unless you later file a non-provisional claiming it, in which case the provisional remains confidential unless needed for priority proof. Also, a provisional should still contain enough detail to satisfy patent requirements or your invention, don’t make it too skimpy, as its content will determine what you can claim in the non-provisional.

Key Insight

A provisional application is a useful first step to quickly secure a filing date for your invention, buying you 12 months to prepare the full application. The non-provisional application must be filed within a year and will be examined by the USPTO. Using a provisional can be a strategic way to get an early date and more time, but ultimately it’s the non-provisional that leads to your patent.

Patent Filing Process in the United States

When preparing to apply for a patent in the United States, it’s crucial to understand the patent filing process as a whole. Understanding the timeline, from filing, to publication, examination, and finally grant, is crucial for managing expectations.

Filing a Provisional (Optional)

If you choose to begin with a provisional application, the process at this stage is relatively straightforward. You prepare a description of your invention including as much detail as you would in a non-provisional, drawings if applicable, and file it with a cover sheet identifying it as a provisional, and the required provisional filing fee (which is significantly lower than non-provisional fees). The USPTO will assign a filing date and application number but will not examine the application for patentability.

As stated before, you receive an official filing receipt with your provisional application number and filing date. This date is your priority date for subsequent non-provisional filings within 12 months. The provisional application remains confidential (not published) and essentially sits in the USPTO’s records. No patent rights are granted from a provisional alone as it merely holds your place. After 12 months, the provisional application expires and is automatically abandoned, if no follow-up application was filed.

Filing a Non-Provisional: Required Documents

When you file a non-provisional patent application with the USPTO, you are formally starting the examination process. A complete non-provisional application includes:

- Application Data Sheet (ADS): This form provides bibliographic data (inventors, title, correspondence address, any priority claims to prior applications, etc.).

- Specifications: A written description of the invention, including background, summary, detailed description, and abstract. This must enable someone skilled in the art to make and use the invention.

- Claims: One or more claims particularly pointing out the subject matter you regard as your invention. The claims define the legal scope of protection.

- Drawings: Necessary if they help illustrate the invention. Drawings must meet USPTO formal standards.

- Oath/Declaration: Each inventor must sign an oath or declaration stating they believe themselves to be the original inventor(s).

- Invention Disclosure Form (IDS): The inventor must provide a list of prior art references they know about. If they don’t have anything to submit, that’s fine. However, it is mandatory to disclose known references in order to file patent applications. When patents go to litigation, this is usually the first thing that an opposing attorney will check to try and invalidate the patent, or worse, seek damages against the patent holder for inequitable conduct.

- Fees: Filing fee, search fee, and examination fee (and any applicable surcharges or extra claim fees). These fees can change, so always check the current USPTO fee schedule.

Once you submit the application, the USPTO will accord it a filing date and an application serial number. You will receive an official filing receipt a few weeks later confirming these details and listing any claimed priority, such as to a provisional or foreign application.

Publication

In the United States, patent applications are published 18 months after the earliest filing date (provisional or non-provisional), following the global standard. The publication includes the specification, drawings, and claims as filed, and is assigned a publication number distinct from the application’s serial number. Once published, your application becomes publicly available through databases such as USPTO Patent Center or Google Patents.

If you do not plan to file abroad, you can request Nonpublication when filing. This keeps your application confidential until grant, unless you later decide to file internationally, in which case you must withdraw the request. Conversely, applicants who wish to disclose sooner may request early publication, usually processed within 3–4 months.

Design patent applications are not published before grant and remain secret until issuance.

USPTO Examination

After filing, your application enters the examination queue at the USPTO. Patent examination, or prosecution, is where a USPTO patent examiner reviews your application to determine if it meets all legal requirements for patentability. This is typically the longest phase of the process. Here’s what happens during examination:

1. Classification and Docketing

The USPTO assigns your application to the appropriate Technology Center and art unit based on the subject matter. It gets placed in an examiner’s docket.

2. Examination

When the examiner starts examination, they will read your disclosure and conduct a prior art search for relevant existing patents and publications. The examiner will check for compliance with formalities and patentability criteria such as:

- Formalities: Are claims properly formatted, drawings labeled, abstracts within length, etc..

- Novelty: Is your claimed invention entirely new?

- Non-Obviousness: Even if novel, is it an obvious variation of what was known? The examiner will apply U.S. patent law to determine if the differences would have been obvious to a skilled person.

- Utility: Does the invention have a specific, substantial, and credible utility?

- Patentable Subject Matter: Is it the type of subject that can be patented?

- Disclosure Requirements: Does your application meet enablement, written description, and definiteness requirements?

3. Office Actions

The average time to first exam action is around 18–24 months from filing, though this varies by technology field and USPTO backlog. The examiner will almost always issue an Office Action detailing their findings. The first action is often a Non-Final Office Action, which will either allow the application or, more commonly, list rejections/objections.

Common rejections include novelty rejections, citing prior patents or publications that anticipate your claims, obviousness rejections, combining multiple references to show your invention would have been obvious, and/or rejections for issues like unclear claim language or insufficient support in the specification. Don’t be alarmed, it is very normal to get rejections in the first Office Action. In fact, the vast majority of applications are initially rejected.

After receiving an Office Action, you (or your patent attorney/agent) will have a chance to respond to it, typically within 3 months (extendable up to 6 months with fee). In your response, you can amend the claims and/or argue against the examiner’s rejections, for example explaining why the prior art doesn’t actually teach all your claim elements or why the examiner’s obviousness reasoning is flawed, etc. This back-and-forth may go on for a few cycles.

If the examiner remains unconvinced after your response(s), a Final Office Action will be issued. “Final” does not mean the process is over, it simply indicates that the examiner will no longer consider unlimited responses as a matter of right. After a final rejection, applicants still have several options: they may file a Response After Final (limited to amendments that cancel claims or address minor issues to place the case in condition for allowance), submit a Request for Continued Examination (RCE) to reopen prosecution and receive another round of Office Actions, or appeal the rejection to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). In practice, most applicants choose to file an RCE if they believe the invention remains patentable, as it allows continued negotiation with the examiner without resorting to appeal.

Allowance and Grant

If the examiner becomes convinced that your claims are patentable, you will receive a Notice of Allowance. This is good news as it means the examiner has decided to grant a patent on your application’s claims. The Notice of Allowance lists the allowed claims and will ask you to pay the issue fee. You must pay this (typically within 3 months of the Notice) for the USPTO to issue the patent. After payment, the application goes into the issue queue. The patent is usually granted within a few months after the issue fee is paid.

On the issue date, the USPTO publishes the patent in the Official Gazette and you receive a patent certificate. The patent is now enforceable property right as of its issue date. In this process, the USPTO will assign a patent number and issue date.

Maintenance

Patents have a finite term but require maintenance fee payments at set intervals to keep a granted patent in force. A utility patent’s term is generally 20 years from its effective U.S. filing date.

Utility patents are subject to maintenance fees at 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5 years after the grant date (USPTO). Please note there is a window to pay these fees. You can pay the corresponding fee in the 6-month period before the due date, or within a 6-month grace period after the due date with a surcharge. If you fail to pay by the end of the grace period, the patent expires prematurely. Design patents are exempt from maintenance fees once granted, and they last their full term without additional payments.

Key Insight

Achieving a patent is a major milestone, you’ve secured a United States patent registration for your invention. A utility patent grant gives you up to 20 years of protection from your filing date. Remember to maintain your patent by paying the 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5-year fees, and make the most of your patent through strategic enforcement or licensing. Patents don’t enforce themselves, but they provide a powerful legal tool to protect your market and innovations.

Strategies and Recommendations for Patent Filing in the USA

In this section, we discuss some special strategies and USPTO programs that inventors and practitioners can leverage to optimize the patent process. These include ways to speed up examination, strategies around publication, and using continuation applications to broaden or extend patent coverage.

1. Prioritized Examination (Track One)

Waiting 2–3 years (or more) for a patent can be problematic for fast-moving industries or startups. The USPTO offers Prioritized Examination, commonly known as Track One, which is a program to expedite examination of a patent application. By paying an additional fee and meeting certain filing requirements, you can get your application advanced out of turn for rapid review.

The USPTO’s goal for Track One is to provide a final disposition (allowance or final rejection) within 12 months of grant of prioritized status. In fact, it often moves even faster. Track One applications on average receive a first Office Action in about 1–2 months after filing, compared to 18+ months normally. Many Track One cases reach allowance in under 6-12 months total.

In order to apply, you must request Track One at the time of filing (or with an RCE) and pay the prioritized exam fee. There is also an overall cap on how many Track One requests the USPTO accepts each fiscal year.

2. Other Acceleration Options

Besides Track One, there are a few other ways to speed up prosecution:

- Petition to Make Special: Available for inventors who are older than 65 or for health or other extraordinary reasons, or for certain important technologies (e.g., anti-terrorism, HIV/AIDS, cancer, or for inventions under DOE pilot related to energy efficiency).

- Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH): If you have an allowed claim in a foreign application (in a participating country), you can request fast track in the US based on that. This leverages work done abroad to accelerate US prosecution.

3. Continuation, Divisional, and CIP Applications

The U.S. patent system is somewhat unique in allowing continuing applications, which are powerful tools for applicants to get more than one patent or try again for different claims from a single disclosure. Let’s break down the types:

- Continuation Application: A continuation is a new application filed while the parent application is still pending, using the same specification but a different set of claims. It keeps the parent’s filing date and allows you to pursue broader or alternative claim scopes. This is useful when the parent patent is allowed with narrow claims, but you want to continue prosecution for broader protection.

- Divisional Application: A divisional is filed when the examiner determines that the parent application covers multiple distinct inventions. You choose one invention to continue in the parent, and file a divisional for the others. Each divisional keeps the same disclosure and priority date, ensuring protection for all disclosed inventions without losing filing rights.

- Continuation-in-Part (CIP) Application: A CIP adds new material to the parent’s disclosure, combining old and new content. Claims supported by the original disclosure keep the parent’s filing date, while those based on new matter get the CIP’s date. This is useful for improvements or additional data but must be used carefully, as new content may face new prior art.

Key Insight

The U.S. patent system offers powerful strategic tools, such as fast-track examination, early publication, and continuation filings, that help inventors accelerate protection, shape market timing, and expand patent coverage to maximize the value and impact of their innovations.

Strengthen Your Global IP Strategy with a USA Patent

Securing a patent in the United States is more than local protection, it’s a cornerstone of a global intellectual property strategy. A U.S. patent enhances your international credibility, supports partnerships and licensing abroad, and establishes a strong priority foundation for filings in other key markets. Because the USPTO’s examination standards are among the most respected worldwide, a granted U.S. patent often strengthens your position before other patent offices.

When you file patent in United States, you also create strategic advantages for entering the PCT national phase in other countries. Many foreign patent offices view U.S. examination results as persuasive, streamlining international prosecution and saving time and costs.

Get your Patent Filed in the United States

Contact us today for a free consultation

References

- United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). Applying for Patents. Available here. (Reviewed on October 2025)

- United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). 1893 National Stage (U.S. National Application Filed Under 35 U.S.C. 371). Available here. (Reviewed on October 2025)

- United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). Maintain your Patent. Available here. (Reviewed on October 2025)

- United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). 1505 Term of Design Patent. Available here. (Reviewed on October 2025)

- United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). Patents Pendency Data September 2025. Available here. (Reviewed on October 2025)

- United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). Voluntary early publication of patent applications. Available here. (Reviewed on October 2025)

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Time Limits for Entering National/Regional Phase under PCT Chapters I and II. Available here. (Reviewed on October 2025)